"The most important thing I have ever learned so far is --- how to learn."

Flo and Thomas respond to their lifelong mentor Jaehn Clare's prompt in this first AskUs reflection.

Once we saw Jaehn’s answer, we both just had to go with it. Rather than responding with a different “most important thing,” we both chose to delve deeper into the idea of “learning how to learn.”

The most important thing I have learned so far is that presence is the key to learning how to learn.

by Thomas Vinton

Mom always said that presence was all we needed when being together. What we did or said was never as important as the fact that we were sharing the same space. Since her departure from this physical plane, I’ve cultivated the capacity to be present to her spirit and receiver her eternal presence.

Roll call: you can answer “here” or “present.” In retrospect I would have always answered “present,” though I always opted for the seemingly less haughty “here.”

I remember teaching myself to tell time on an analog clock during naptime in kindergarten. My body was not present to sleep, so my mind became present to the big hand winding its way down to the six, which signalled my chance to go out to play. Play was an act of pure presence and an opportunity to learn without the burden of perceiving knowledge as an object of study. Riding around the merry-go-round I heard “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head” in a loop. I taught myself that music didn’t go in a straight line, but like the hands of a clock, in a circle (except the trumpet solo at the end; it was a tangent - not that I knew the word, just the concept).

By the time I got to geometry class a decade later, my presence to the squeaky turntable I rode round and round and the leaping off and running in a straight line probably helped with the collection of facts and such required of high school students. The clock I studied also taught me early on that I would be required to be “here” whether I was “present” to the task at hand or something more interesting to me at the moment. For example, I did learn how to take naps in high school math class.

The math teacher was present to his chalk, chalk board, lesson plan, and knowledge, but he was apparently not present to my classmates or me. Otherwise he certainly would have understood at some point that having us sit quietly in rows while he droned on was as an utterly useless way of teaching math and a perfect way to make sure I would never become present to the marvels that true math enthusiasts rave about. Dad would describe with great enthusiasm the joy of doing long division in his head. I’m sure the motion graphic artists had a field day with A Beautiful Mind.

One university math expert called me into his office and declared, “Never have I known a scholar such as yourself to be so gifted in the humanities and so pathetic in physics.” I was in an eclectic program that encouraged cross-pollination between the “arts” and “sciences,” so he and I had an unusual vantage point in the often segregated sphere of higher learning.

His presence was a model for me on several levels:

His passion for science’s place in society ignited mine.

His presence in his conversation with me entailed being brutally honest.

His attention to detail in the practice of science made it clear to me that I would not be present to that practice after finishing the trimester.

Similarly, when I tried to get permission from my economics professor to join an advanced class necessary for me to enter international business school, he flatly responded, “I cannot in good conscience endorse this path. If you try to enter the private sector as a business person, you will neither have time to play another musical note, nor the capacity to earn a dime.”

I went on to study and work in film and music production.

For these teachers, presence to the student meant encouraging me to be present to my gifts rather than obsessed with my shortcomings. Easier said than done. I would stumble throughout my career aiming to be practical rather than lost in a chaotic creative process. I have probably spent more time working on spreadsheets than actually pursuing artistic interests.

Even David Byrne admitted to this neuroquirk during a live interview at SXSW 2001, which I gleefully attended as a volunteer film crew member thanks to having recently lost my practical day job (a creative position which evolved into an administrative one). When asked what he thought about running Luaka Bop Records, he confessed that his biggest challenge was to go into the studio to make music because he could spend hours in the office doing busy work. Twenty-two years later, I scratch my head wondering how I could hear all these guiding words and still spend so much more time being present to the clock on the wall than to the very playground that would make the world more present to what I have to offer it.

Which is why I am present to you now.

I am committed to presenting myself in a viable format to the world. My presence here is my present to you. By representing a creative journey in a multitude of media, including what I perceive to be the tangents, I enter a field with you and Rumi that is not only beyond right and wrong, it is also beyond the need to plan, to work, or to do, paradoxically allowing me to plan, to work, and to do without judging myself for it. In other words, for all the time I spent not doing my art, I can forgive myself because even that time was part of the craftwork I have at my disposal to present, an opus similar to outtakes, a distressed treatment of a piece of furniture, or a glitch in a pop record like California Dreamin’ with its chorus that comes in early.

Hold on a second; I’ll be right back.

…

I just spent a moment looking for the source of a brief story I’m about to tell you. Ordinarily I might spend up to an hour looking for something like this. But right now I feel like I’m running out of time, and the main point is so important to share with you, that I’m going to let somebody else figure out who told it first.

If it hadn’t been for all those hours I spent hunting down facts, I never would have learned to stop looking for them now.

The apprentice asks the master (let’s say Confucius for the sake of argument), “What’s the better path: planning ahead or being spontaneous?”

“The answer is that it doesn’t matter. The only important thing is to be present.”

And now Flo is really going to break it down for you.

Essential Components of Learning

by Flo Vinton

Thank you so much Jaehn for challenging me to reflect on what I’ve learned about learning. I’d first like to acknowledge that learning is a dynamic and diverse process that takes place in a multitude of brain and body configurations. For me, personally, with over 52 years of learning and 30 years of teaching, I’ve noticed 5 essential components:

Willingness: For true learning to take place, one has to consent to receiving it. Nothing stifles learning more than being forced to do so.

Meaning: When someone understands why they are learning a specific skill or concept, they become the agent of their own education and transformation and more eager to acquire new knowledge.

Experience: The most efficient way to learn is by putting it through the senses into the body. A good example is that receiving information about an orange by way of descriptive words and beautiful illustrations cannot compare to touching the spherical fruit, feeling its uneven texture, peeling it, smelling its fragrance, tasting the sweet juice, and playing with the tiny sacs of nectar between your teeth and tongue, a process that forever fixes the understanding of what an orange means to you.

Mistakes: “There are no mistakes, only lessons learned,” it’s been said. Trial and error are part of the process of learning. It is important to recognize the learning that takes place when a toddler falls down. Having our body or ego bruised allows us to suspend judgment and reframe failure as a positive and productive part of the learning process.

Trust: Having faith and being confident that what I’m learning fulfills a need and contributes to my wellbeing certainly facilitates illumination.

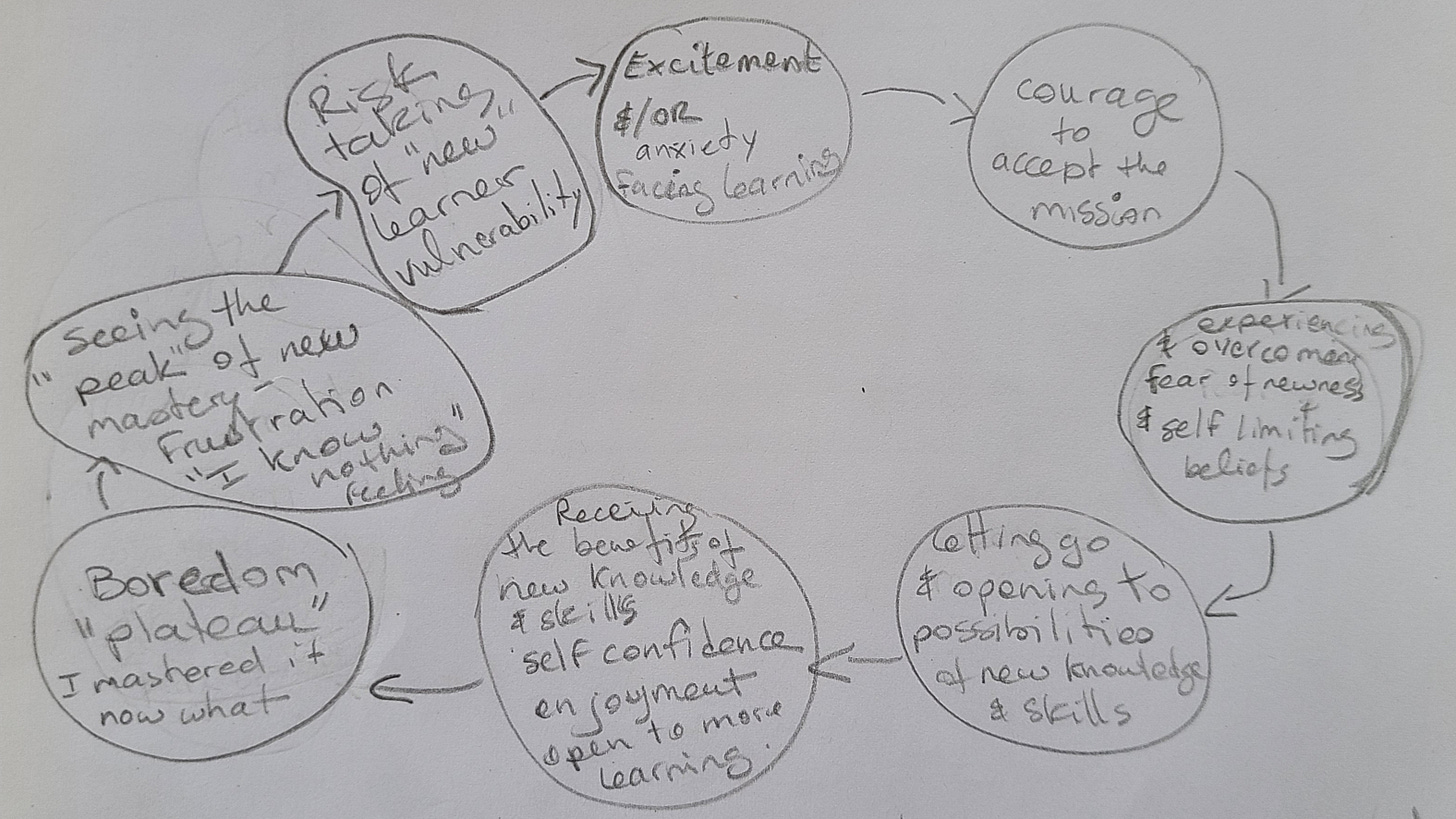

I have come to understand through my students’ and my own experiences that learning comes with an emotional cycle that merits one’s attention to support healthy attitudes toward the process:

Learning is inherent to humans, and as a mom and teacher, the best thing I’ve learned how to do is to stay out of the way of the natural learning flow, supporting with encouragement, neutral feedback, and unconditional love.

Thank you for responding to my question with such deeply personal reflections.😍